+Kitteh Equaliteh: "All you said about chimpanzees is that we have higher intellect and we shouldn't take our moral queues from them (ref. goo.gl/3m3we). I never said we should take moral queues from lions. You still haven't answered my question. Let me boil this down even further. If animal lives are valuable why aren't you trying to stop other carnivores such as lions from killing animals immorally?"

It is an interesting philosophical question that you're posing here +Kitteh Equaliteh, and I did not mean to be coy before in my response; I earnestly thought I was answering your question. In essence, you're asking why it is that I am arguing against humans killing other animals, but why I'm not concerned about non-humans killing other animals, right?

The question of whether it's "right" or "wrong" to kill is always a moral question, but morality does not exist in a vacuum; by definition, it always has context. For example, it's immoral for a human to kill another human -- except in defense of their life, or when killing a person is the action that causes less overall harm, or any number of other "special case" conditions. Similarly, the particular people involved in a scenario also change the moral implications of an action; e.g. we don't treat it the same way when a child steals as we do when and adult does, and we make these adjustments in judgment specifically because of the capabilities and expectations in play regarding each "type" (if you will) of individual in the scenario.

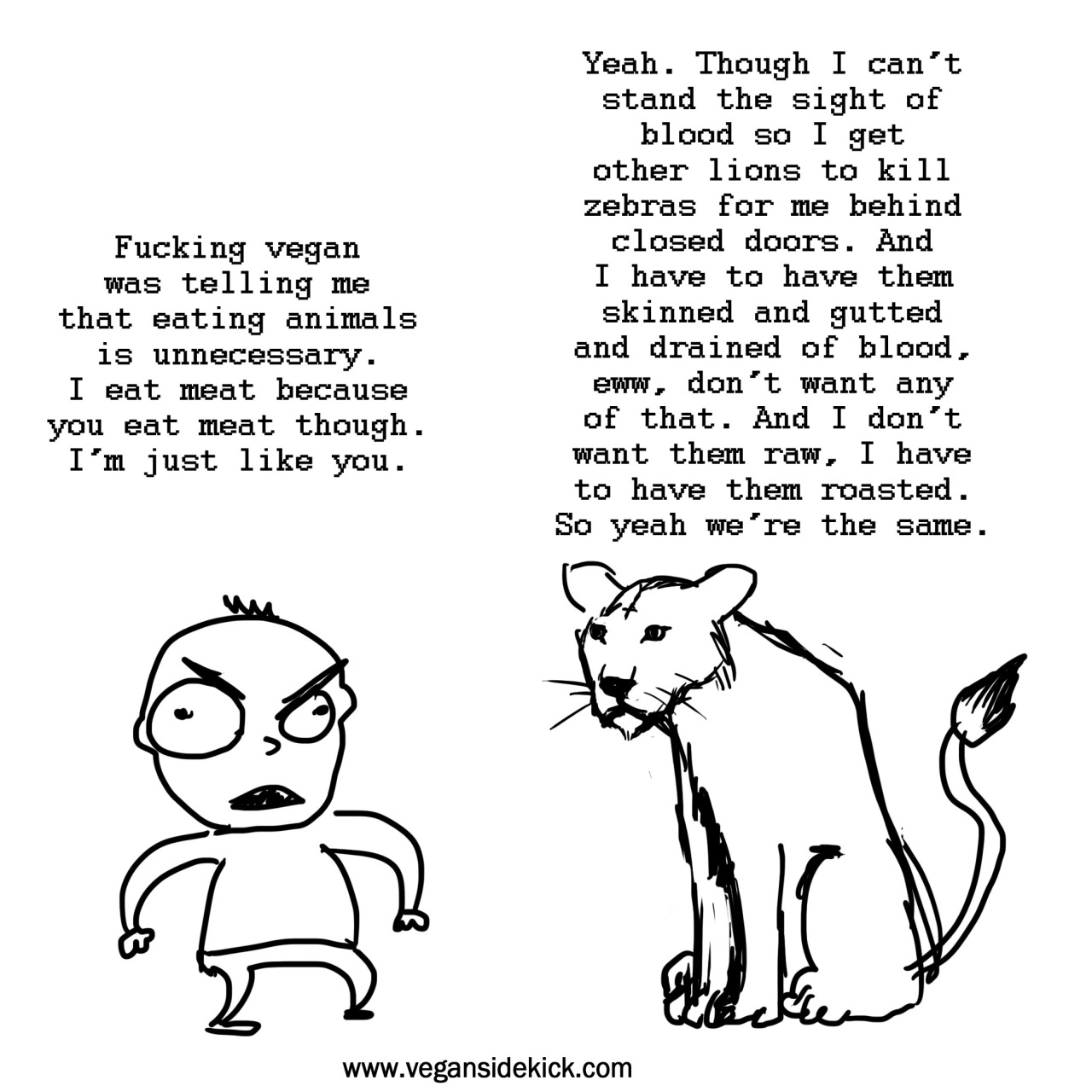

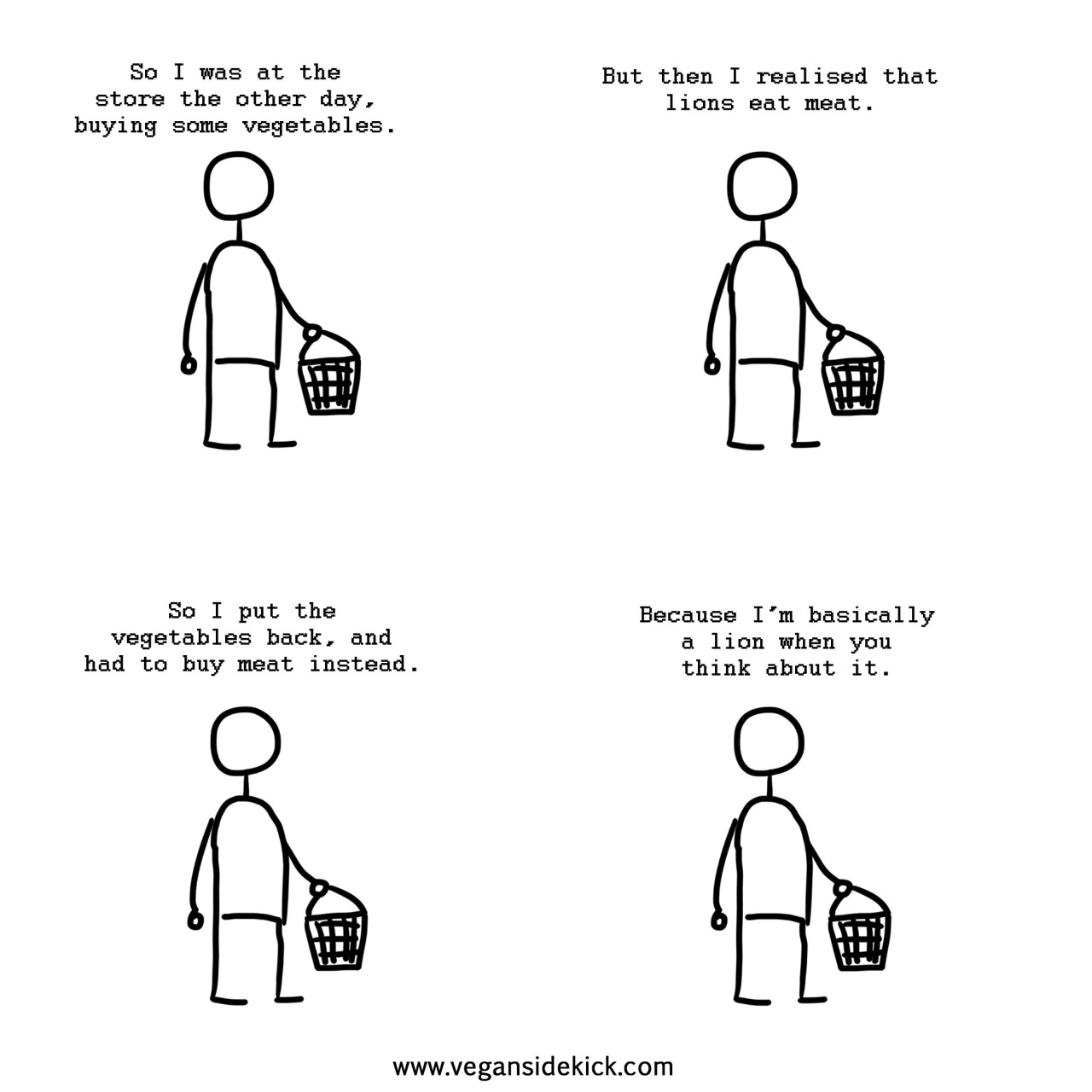

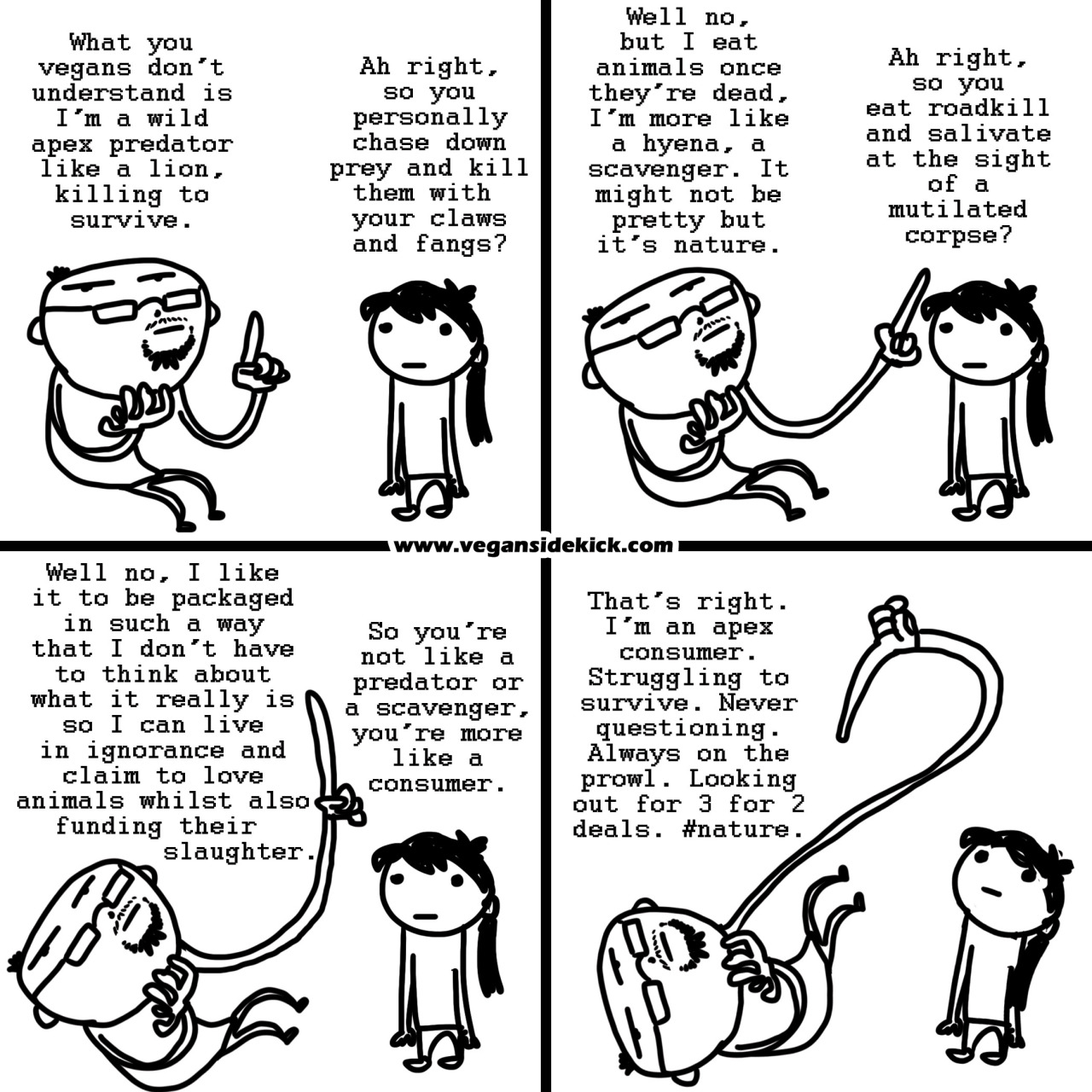

When we look at animals, there is a very different context involved. They are not subject to anything like the same conditions as ourselves, and live in a completely different context. For example, the lion you mention is an obligate carnivore, and will literally sicken (and possibly die) without eating animals, but even that condition does not effect our judgment of his or her actions. After all, it's not like the lion can be reasoned with in the same way that a human can, and it's not as though the lion can (or would) justify his actions to others. As such, the lion's actions cannot be judged to be "right" or "wrong" from a moral perspective. By contrast, when we consider the lion's prey, it's not so much a matter of whether its context changes the value of its life (which would seem to be something that remains constant in any particular case), but rather is a matter of how its context changes our (meaning "humans") responsibility to that life. There are several analogous situations we might consider in order to evaluate how context changes our obligations to these animals.

First, we might consider a house cat hunting a mouse. When my own cat is stalking a wee creature, I do whatever I can to save and release the would-be prey to "the wild", and I do this because I have some level of investment (or responsibility) regarding the actions of my cat (and because I also have empathy for the mouse). I don't feel similarly responsible for the actions of my neighbors' cats, though I might council them to consider being kind to mice and saving them; it's not that my empathy for the mouse has changed or that the value of its life has altered, only that the applicability of my influence on the situation is modified by the context. In effect, I am (usually) succeeding in stopping my cat from killing animals -- not because it's immoral for her to kill, but because it's immoral for me to allow it to happen if I can prevent it.

Second, we should consider the plight of "food animals", being raised in nearly universally abusive situations and being killed by humans with dubious justifications. The intrinsic value of these creature's lives are unaltered by their context, which (to my thinking) makes these killings an immoral act. However, I cannot prevent the machinations that are causing these deaths all on my own, so I'm seeking consensus from others regarding the morality of these actions, and am soliciting their cooperation to stop it. In effect, I am actively attempting to stop humans from killing animals immorally.

Third and finally, we have the lion and its prey. In such situations, there is no moral dilemma that I can see which would cause me to seek out the hunting grounds of the lion and prevent him or her from killing. The intrinsic value of the prey animal's life is unaltered by his or her context, but it's hard to see where a moral imperative for human intervention might come from in such a situation. For reasons vaguely like why we consider the actions of children different than adults, so it is that we consider the actions of non-humans different than humans; the capacity for reason is clearly part of the equation when considering the morality of a situation. On the other hand, if a lion is chasing down a human, I'll do everything in my power up to and including killing the lion (as a last resort) in order to prevent this, specifically because I have the same moral obligation to any random human that they have towards me; in that situation, the lion's actions and the lion's "prey" carry a specific moral obligation on my part (assuming I have the capacity to act on that obligation).

For myself, I'm very interested in the question of whether it's immoral for humans to kill non-humans, which is why I engage these conversations so enthusiastically. I'm keen to find out what other people think about such topics, and to discover if there's some flaw in my reasoning on this. However, for the reasons just described, it seems as though the actions of a lion have very little applicability to that conversation.

Does that make sense, do you think?

—☆—★—☆—★—☆—★—☆—★—☆—★—☆—★—

This post is one in a series in which excerpts of discussions on veganism from other threads are reposted (or paraphrased) for the sake of expanding the conversation. As always, your thoughts and questions are welcome. See the full collection via the #spommveganchats hash (or perhaps with a more robust search, such as goo.gl/JoxZC).

(for anyone requiring/desiring more context, the original conversation can be found at goo.gl/A6RFrx)

#vegan #morality #ethics #equality #animalrights